INDEX || NEWS || INFOS || STAX TODAY || FOCUS || ADS || LIST || LINKS || PHOTOS || E-MAIL

BLACK MUSIC, October 1977, Vol. 4, Issue 47

‘He didn’t do anything, you see. He just played’

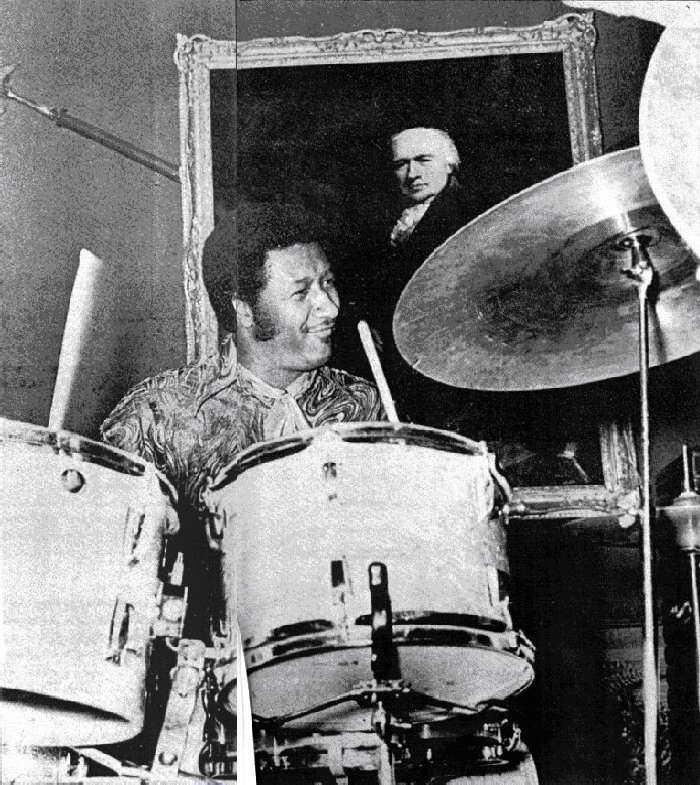

Two years ago this month, Stax' legendary drummer, Al Jackson, was shot dead at his Memphis home. On this anniversary of his tragic and untimely death, Valerie Wilmer profiles the man and examines his influence.

The news that Booker T and the MG’s have started touring again in America will be greeted with some anticipation by all those who admired their exclusive brand of tight funk. Whether the group's new drummer, Willie Hall, formerly with the Isaac Hayes band, will live up to the standards set by his predecessor, Al Jackson Jr., remains to be seen.

However, now is a good time to examine the contribution made by the former Stax house drummer whose death, when he was shot dead at his Memphis home in September 1975, left the music world stunned. Jackson played on countless significant records by artists such as Otis Redding, Johnnie Taylor, Al Green and Wilson Pickett -not to mention Rod Stewart and Aretha Franklin- and his impeccable taste, metronomic ability and funky down home beat were a foregone conclusion in the business. His death left a gap that no-one could fill. BBC Radio London dee jay Charlie Gillett's reaction was to devote an entire programme to the art of this, the finest f*** all rock drummers. As Charlie said, there is not a single drummer out there who has escaped Jackson's influence. The official story was that the Memphis-born drummer had disturbed raiders at his home, but those around him had other ideas. His death came the day before he was allegedly due to testify at a court hearing concerning Stax Records' bankruptcy, and that was more than something of a coincidence to some people. There was, however, no truth in the rumour that Jackson planned to testify against Stax, despite the fact hat they owed him, a substantial sum in royalties. In fact, he was not even supposed to have been in Memphis on the day of the shooting. However, to this day, no further light has been shed on he incident, despite extensive police investigations. It is a mystery that remains unsolved.

Because of the complications that followed the actions of one of Stax' main creditors, a Memphis bank, who backed a truck up to the studios and loaded it with any tapes they could lay their hands on, people have been reluctant to talk in Memphis concerning the situation at the once prosperous recording company as well as the matter of Jackson's untimely death. People want to keep their jobs in this once booming music town. One of my informants even tried to change the direction of my enquiries with the suggestion that Jackson's death might have been brought about by his habit of flashing a large wad of notes -anything other than the possibility that the drummer's killers were, in fact, known to him.

Lips may have been sealed regarding the whys and wherefores of the tragedy, but there was no mistaking the horror and pain felt by Al's associates and by those who loved him. MG’s bassist Duck Dunn, probably his closest friend by virtue of the similarity of their natures, put the general feeling into words: "All f these years you play with somebody and you never appreciate them. It's like a woman. You take 'em for granted and you never realise how good they were. 'You just go along, you play with them day after day, and they do things that are just daily things. That's the way Al was when he played –maybe that's the way I was with him. And you never know it till they've gone and you miss ‘em. Then you want 'em back.

"Oh, there's plenty of great drummers, but playing with Al was just like getting up on time. Like every day you have your daily routine -you get up at 8.30 and you have your coffee, or you get up at 10.30 and you have your coffee. Well, when Al made times and things, he made times. He made you make times with him. It just got to be that way."

Talking to people who had been close to Al Jackson, a picture gradually emerged of a simple man who loved life, uncomplicated but firm in his resolve whenever he put his mind to something. Despite his universal recognition as a master drummer, especially for his imperturbable time-keeping, he never considered himself as great as did his admirers. Possibly this self-criticism stemmed from having grown up in a jazz-and-blues milieu, though there was no doubt that he related more to the relatively lucrative world of the studios than to jazz. "Al Jackson was a good drummer but he was a money drummer," said saxophonist George Coleman who grew up in Memphis a few years earlier than Jackson.

The drummer's father, Al Jackson Sr., was a bassist who led a formidable big band for many years and, at some time or another, the younger man played with the city's leading jazz lights, among them saxophonist Charles Lloyd, pianist Phineas Newborn and bassist George Joyner. His idols were people like Philly Joe Jones and Elvin Jones. On one occasion he sat in with the Max Roach group. Nevertheless, he was happy in his chosen field and had no desire to be playing jazz.

The point was that in his own estimation, he made it too big too fast. Probably he knew so many gifted drummers who were never able to make the transition from bebop to the particular Stax kind of sound, best described as "down home contemporary." One man he particularly admired was Joe Dukes who had played in Willie Mitchell's band before Al. Jackson once described him as "the damnest" drummer he had ever met. Yet it was Dukes who told him "You got to be lucky! You're not playing shit but you've gotten over." Dukes' reaction may have been sour grapes or he may have been joking, but Jackson was reportedly hurt by his comments. He felt that compared to Dukes, well known in jazz circles, what he was doing was nothing special.

Willie Mitchell used Al Jackson on several of the Al Green dates he produced for Stax. He described him as "basically a Memphis drummer, he wasn't a rock drummer. By that I mean that his drumming had what we call `The Memphis Sound'. He was a downbeat drummer. Al played with lots of rhythm, heavy. He'd really swing -you know, that kind of drummer."

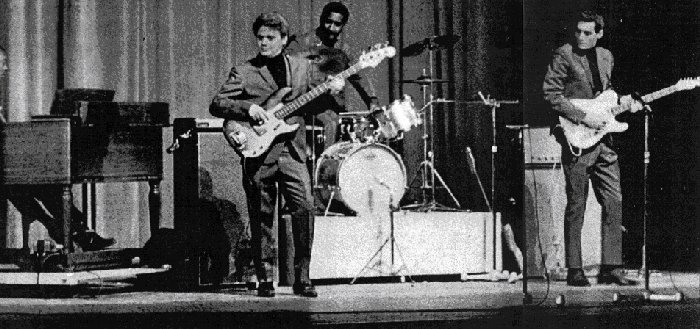

The MG’s -it stood for Memphis Group -were unique in that they were an integrated band playing what was essentially black music and doing it in the South. Steve Cropper, who wrote and produced all the Otis Redding classics, came from the Ozark Mountains in Missouri. Like him, bassist Duck Dunn was white. Booker T. Jones, the youngest member of the group, was black like Jackson.

"Some people might be startled that guys like Steve and Duck can play real soul music," Jackson once told Phyl Garland of Ebony magazine. "But when it comes to this soul thing, people have to remember that whites, particularly in this area, have their own kind of roots in country and western music, while we as blacks have ours in blues, gospel, R&B or whatever you want to call it. When you get a white guy who is flexible enough to blend the feelings from those two different kinds of music and to come up with his own thing, then you have something that is really formidable."

On the recordings made at Stax, Jackson is always unavoidably outfront although he was recorded in the background. "He comes out as the reverse of what he was doing," said Steve Cropper. "His drums in the mix came out on top of everything. When, in reality, he was playing under the song to complement it, on tape he came through like gangbusters!" Jackson played as an equal part of a group that was egalitarian in its structure and methods. Whoever came up with an idea on a session, it would be tried out before being rejected. The drummer meshed effortlessly with Booker T's clean, driving organ and Cropper's funky, blues drenched guitar. He held the time rocksteady while Duck Dunn played his bass like another drum, the one the people danced to. "I'd like to say that I created all those basslines but I didn't," said Dunn. "I had plenty of help from Booker and Steve." And all three of them had plenty of help from Jackson, an older man who brought his considerable expertise and common sense to the music and was always prepared to sit down and talk to the others when things went wrong. Where so many rock drummers instil their playing with frantic urgency in the mistaken belief that this is synonymous with excitement, playing loud and hitting hard for the sake of it, Al Jackson knew how to make love to his drums. He always held back till the right moment. "He had such a delayed backbeat that when he came down on a beat it felt like it wasn't going to get there," said Duck Dunn. "And when it got there, it just … ooh!

"With Al you just had to kind of wait on him and wait till he'd come down on the beat to catch him. And, that, to me, was his secret. I mean, when you played with Al, you played with Al. Al could make you look bad because if you ran off and left him, he didn't care. A lot of drummers, if you start rushing, they'll go on and pick up the time, but Al wouldn't do that. He'd just keep it right where he thought it should be and he'd make you look like a fool. But he was right ninety per cent of the time."

In actual fact, some of the MG’s tunes were intended to be played harder with more of a so-called rock beat, but Jackson changed them by insisting that they be played his way. Sometimes the others would have preferred the music to be a little more rock oriented, but Jackson was firm in his resolve to do things his way, which meant more straightforward. At the time, the others were unhappy about it. Later, playing the records to himself, Duck Dunn was to realise just how exceptional their music had been. "I used to listen to other albums and wonder why our sound wasn't as good as theirs. Then after the band broke up, you could hear everything each of us did. Al played to the point where he didn't clutter up anything. He played like a singer. He had a part and he did it. They do that nowadays, too, but back in those days it was kind of new."

In the studios where gallons of beer were consumed during the course of a session, it was always Jackson who would count off the time. The others looked to him to do that because of his incredible, metronomic sense of time. He has been described as dominating and argumentative yet he could take control without being egotistical. "He played very complementary drums," said Steve Cropper. "He played for the people he was playing behind where a lot of drummers play for the drummer -you know, `I want to be the baddest drummer in town and I'm gonna play my best licks'. And that's their whole life's attitude, to be the best drummer. Al's attitude was not like that at all. He didn't care about, being the best drummer, he wanted to play something that would make the song happen."

According to a former Stax employee who was very close to Jackson, he never believed in the drummer being the "showpiece". "The reason so many producers would call him was because he had such a terrific sense of timing. He would never run off with the songs, he could always pocket it."

Steve Cropper confirmed this : "If you didn't change tempo in the course of a day, you could just edit the first track of the day with the last one and the tempo would not move," he said. "He was impeccable and he knew it. I mean you could go out and have lunch, you could go take an hour, and you come back and you say `OK, count it, Al'. and it would be the same exact tempo as when you left it an hour ago. I've never worked with anybody else that did that dead on time."

Cropper paid tribute to Jackson's simplicity and the fact that he always knew what song he was playing. This was in keeping with the Stax dictum that every song should have a meaning. "We like for the artists to be able to feel the lyrics of a song, to live them," vice-president Al Bell once said. It was the innovative saxophonist Lester Young who once said that the improvising musician should always know the words of any song he used as a vehicle and Al Jackson was no exception.

Cropper said : "A lot of drummers, even though they have music in their head and everything, are not really aware of what the song is, what it's about and why it's being done in the first place. Al always had the insight of what the song was trying to say. And he knew the melody. He would hear it a couple of times and the melody would lock in his head. He could almost sing you the song, he'd listen to the singer's approach and what he thought they were trying to get out of it, and he played the drums to complement either the pulse or the beat of it, the excitement or the emotion. That's the way he played, but he played it real tasty and real simple."

Duck Dunn summed it up : "Al played drums like a guitar player played guitar. Al played drums like a singer sang. He had moods -you listen to the Al Green records, the ones he did, and the lift on those records! He went soft, he kept it down, and when it needed to move, he moved it."

Jackson was also notable for his ability to shift effortlessly from pattern to pattern, a skill that came naturally to him yet was nurtured through playing with his father's big band where accenting the brass and so on were necessary functions. Such virtues added to his overall competence and made hire an allrounder. His versatility expanded in the small groups and trios of the jazz world. "He had fast hands, a good foot, he knew rhythm well." said Willie Mitchell. "He was a very sensible drummer."

Today, with the spotlight focused on flamboyant set-ups and sartorial idiosyncrasies in the drummer's camp, such attributes often take a back seat. Yet one wonders how many of today's overnight wonders with their snakeskin boots and dozen or so tom-toms reaching halfway round the stage could sustain the disaster of a stick going through a snare drum in the middle of a concert and carry on without missing a beat. This happened on stage while the MG's were backing Otis Redding and recording the `Live In Europe' album. Redding launches into "Respect" and the snare head goes, but Jackson keeps on going, catching his rimshots off the tom-toms as though nothing had happened.

Jackson once outlined his feelings regarding the unnecessary accoutrements of show business. "What do they buy -the clothes or the individual? Have you got to dress everything up for it to be accepted? Can't it be accepted in the raw? If it can't be accepted in the raw, then it's not worth being accepted any way. Then you're making it all phony. You're taking away the true identity. But some of us started out with one gift in life that we should be proud of and that is being black, because the day we were born into this world the truth was slapped into our faces!"

Jackson was not even fussy about the make of drums he used or how the kit was set up. His only preference was for a Rogers' foot-pedal. He would sit down and play however his drums were tuned, and even let other people tune them for him. Stax engineer Ron Capone, himself a drummer, would tell him, "Al, that drum needs tuning," and he would reply, "Hey, Bonnie, come out here and tune it."

"He believed in me as a drummer," said Capone. "And he would not touch the drums. I had to go out there and do everything for him, then go back into the control room and he'd go on playing." And whenever he did tune his own drums, he would do it with the engineer in mind rather than his own ear, the mark of a self-effacing professional who knew where his priorities lay.

Sometimes in the studio Jackson would play standing up, one foot on the bass drum-pedal, the other keeping the hihat closed while he played on it with the sticks. From this vantage point he would build an intense rhythm and inspire the MGs, or anyone else in the studio, to greater heights. He and Ron Capone also established a routine that is still used by the young drummers in Memphis today. When the musicians prepared to cut the master tape, Capone would shout out, "Hey, Al, how are we going to cut this?" Jackson's reply, preserved on the original tape in front of a million Stax singles was always the same : "We're gonna cut the shit out of it!"

Al Jackson played the shit out of everything he did. Listen to "Green Onions", the MGs' first hit. The reason for its phenomenal success was that Jackson just cooked away from start to finish. However tired he was, and that band frequently worked from ten in the morning till well past midnight, six or even seven days a week, Al Jackson never let up until the music was finished. He was, as they say, good to the last drop.

Jackson worked in his father's band and with trumpeter Gene "Bowlegs" Miller before he joined Willie Mitchell, then an important local bandleader, in 1959. This gig lasted for nearly nine years and was so highly regarded by Jackson that if a Mitchell date coincided with a record session in the early days at Stax, he would let Ron Capone take his place in the studio rather than miss out on the "proper" job. This continued even when the MGs' first hit "Green Onions" was riding high. Capone went on the road with the group while Jackson played with Mitchell.

Gradually, though, his attitude towards session work changed in common with the others involved at Stax, and Jackson started working daily in the studios. Because he was fractionally older than the other musicians, Jackson always acted as though he had a sense of responsibility towards them. In particular he took care of Booker T, relating to him in a paternal fashion as the organist was the youngest in the group and, furthermore, both of them were black. "In that group, Booker was the only one that needed a spanking now and then," said a close friend. "That was because he was a baby and Al was the one who did it. I feel that he pretty much kept all of them in line because he was the older one and a lot more settled. His whole objective was to establish something viable, something he could bank. It's as simple as that."

Although it was Cropper who produced Otis Redding's records and Booker T. who produced other artists, someone close to Jackson suggested that he, in fact, produced any band he worked with.

As a result of his superior years and reputation, young drummers would flock to Jackson's side for pointers and advice. One of them was Carl Cunningham who went on to play with the. Bar-kays, the group that toured with Otis Redding when the MGs had to stay in the studio. Cunningham, who was killed in the plane crash with Redding, started off by shining shoes in the barbershop next door to Stax. He would come into the studio and watch Jackson play, then when the drummer went into the control room to listen to a playback, Cunningham would sit down at the drums and play the beat he had just been playing. He did 'that for three years, then ended up backing Redding himself.

The other drummer who followed Jackson's every move was his new replacement, Willie Hall. Where Jackson had actually taught Carl Cunningham, Hall listened. "He studied AI like a clock," said Cropper. Hall made his debut in the new Bar-kays, reformed after the tragic accident, but Ron Capone had his doubts about the young man's abilities. "I said `Willie Hall will never make a drummer'. I even told Willie that, he was that bad. But he was determined he was going to make it. He used to come on that drum stand that we had in the studio and sit behind Al Jackson and just watch his hands, his feet, and just watch him. And from out of nowhere, and even working with him every day, I walked in the studio and there was Willie Hall, an incredible drummer.

"In fact he was so incredible that I could get a better sound on him than I could on Al. He turned out to be the best recording drummer I have ever recorded. He plays perfect balance. You know, some drummers have heavy hands and light feet, some of them have heavy feet, and some of them are equally balanced and can play everything just right so that it comes out evenly recorded. Willie Hall was like that, but he learned from Al Jackson."

The collapse of the Stax empire in 1975 came as a shock to the music world, yet those close to the company already knew that all was not well. Cropper had already left to set up his own TMI Studios in Memphis and Capone had gone with him. Despite Jackson's entreaties and reasoning, Jones had gone out to the West Coast. Only Dunn and Jackson remained. Both of them stayed with Stax right up to the end but, fortunately for the drummer, new vistas opened up for him at Hi with his collaborations with Willie Mitchell on the Al Green productions.

For a long time, it was assumed that Jackson was the drummer on all the Al Green tracks, for Howard Grimes is so similar to him in feeling and his impeccable timekeeping. On `Simply Beautiful, where the drummer uses only his feet on bass drum and hi-hat, right up till the last chorus, it could well have been Jackson, the master of the subtle approach. But it was not, and this points to the possibility of a Memphis school of drumming being not as remote as some would make out. What is more, Howard Grimes is also responsible for the delicate conga beat introduced in "Let's Stay Together" which has been copied from coast to coast ever since. Later on, after Jackson's death, however, Duck - Dunn listened to the Al Green records to try to make an objective assessment of what Jackson had been trying to say each time he stopped the bassist from rushing the tempo. "All you had to do was listen," he said. "The ups and the lifts and the feelings he played on those records. I got what Al was trying to do out of those records. It's just a shame he's not here now."

At the time of his death, Jackson was working on a Major Lance production and his own album. Two weeks previously, the MG’s had got together for the first time in four years to discuss the possibility of getting together again. It was ironic that the tragedy should have occurred when it did.

Almost alone amongst the Stax session men and other employees, Jackson invested his money wisely. Ron Capone reckoned that the drummer was probably better off than anyone else in the company, co-presidents Jim Stewart and Al Bell included. His main source of revenue outside of the recording industry were the eight or so oil wells that he had invested in. Others, including Cropper and Capone, had also invested, but it was Jackson whose gamble paid off. In addition to this, the drummer owned a large filling station (formerly his father's property). Money was not one of his problems.

Some people are dubious that Jackson's killers will ever be brought to trial although rumour has long been rife as to their identity. As one friend pointed out, "This is also the South. AI was worth a million dollars alive, but dead, cash assets, he was worth around 250,000 dollars. Now I may be wrong, but experience and just plain vibes lead me to believe that the average white attorney involved in the situation would consider it an opportunity to rip off. Their attitude would be `He was a black man and he didn't have any business with that kind of money, anyway!'."

Al Jackson was essentially an honest, straightforward drummer, just as he was an honest, straightforward person. The only thing he disliked about the record industry was the dishonesty that prevails. "If he had been able to express his talent in a business that was much less corrupt, he would have been an even happier person," said someone who was close to him. "He didn't like having to play games in order to be' fairly compensated for the work he had done."

Al, personally, was super," said Steve Cropper. "He was a good guy and a good friend. Al was set in his ways. He knew what he wanted out of life and what he wanted to do, and he sort of followed that trend and did it. He didn't mind saying something. Al was not the kind of guy that would lay back and wait on everybody else. If he felt like something was wrong, or felt like he had a feasible idea, he would come out with it right 'in front. No, Al was super, he was a nice guy. We lost a real good friend there and a good musician."

It was left to Duck Dunn to come out with the most fitting epitaph. "I'd go out and I'd play with other drummers, jam, and they'd always ask me `How does Al do this?' and `How does Al do that?' They wanted to know how he tuned his drums. Other drummers tuned their drums better than Al ever hoped to tune 'em.

"He didn't do anything, you see. He just played."

Valerie Wilmer

Go back to previous Al Jackson Jr. FOCUS page

INDEX || NEWS || INFOS || STAX TODAY || FOCUS || ADS || LIST || LINKS || PHOTOS || E-MAIL